Taking a collateral history is the third core component of assessments. Insight can change considerably over the course of a psychotic illness and its treatment. Concentration is subjectively normal (patient unaware) but objectively impaired (for example, the patient cannot recite the months of the year backwards). Cognitive impairment, tested at the bedside, can present in the early stages of psychosis, but gross abnormalities may alert the clinician to learning disability or organic pathology. Suicidality (thoughts, intentions, actions) must always be assessed by asking questions like, “Have the voices suggested suicide?” Other abnormalities of thought (obsessions, overvalued ideas) and perception (illusions, misinterpretations) are common. An anxious or perplexed affect may impact on actual behaviour. Affect, the outward expression of mood, is unlikely to be normal in these patients: flat affect may be the most obvious sign of negative symptoms, but there may be others (box 2). Mood should be noted as normal, depressed, or elevated.

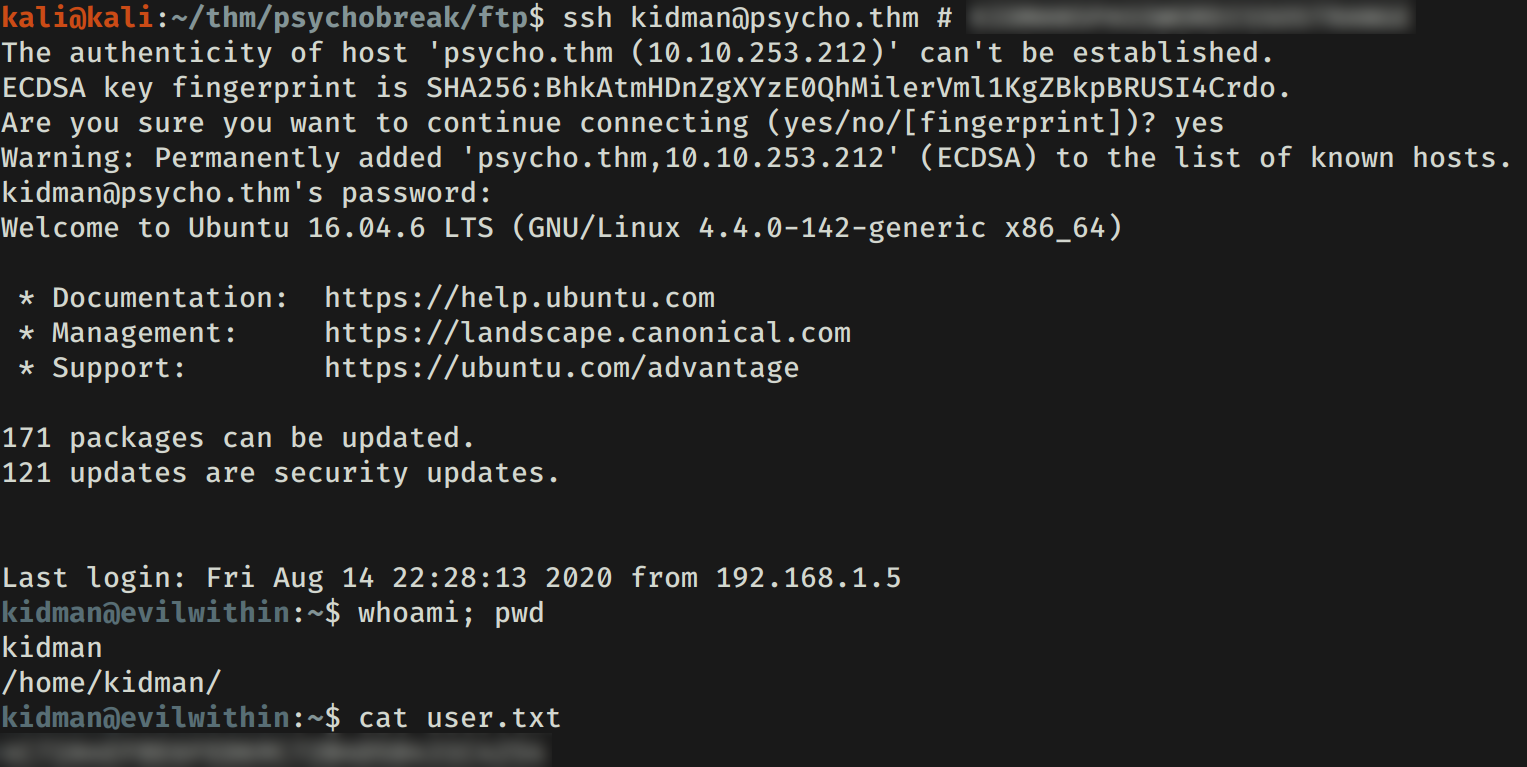

Random changes of the subject (loosening of associations) and new words (neologisms) are best written down verbatim. Speech will be disorganised if thought disorder is present (box 1), and with predominant negative symptoms (box 2) conversation will be stilted and difficult. Altered consciousness is highly unusual in non-organic psychoses-intermittent clouding indicates delirium and this or other impairments require urgent medical investigation. Other motor signs (catatonia and negativism) are rare in Western settings. The patient's general appearance and behaviour may indicate overarousal and hostility (as a result of positive symptoms) or irritability suggestive of elevated mood. The primary diagnosis may be revised weeks or years later (box 3), and thorough documentation improves diagnostic accuracy now and later.

There are explanations of psychotic “symptoms” other than the biomedical model of this review medicalising psychosis as “an illness like any other” increases both public pessimism about outcome and the stigma attached to people with psychosis. Taken together, therefore, acute psychosis is one of the most common psychiatric emergencies. Other causes of organic psychoses are neurological disorders (epilepsy, head injury, haemorrhage, infarction, infection, and tumours) and most causes of delirium. 1 Psychosis occurs frequently in all forms of dementia including Parkinson's disease. The misuse of substances, notably cannabis, 5 raises the prevalence of psychotic symptoms further-substance misuse partly explains the 10 times higher prevalence of psychosis in prison populations. Bipolar affective disorder has a lifetime prevalence of 1.3-1.6%, 4 and it is characterised by episodes of psychosis during both high (“manic”) and low (depressive) relapses. 3 Some people who become depressed (one in five of us over a lifetime) also develop hallucinations and delusions, related to and “congruent with” their low mood. w1 Independent of known associations with migration and ethnic origin, increased economic inequality in areas of high deprivation also predicts a higher incidence of schizophrenia. people, and a lifetime morbidity risk of 7.

2 Schizophrenia has a one year prevalence of 3. Psychotic symptoms had a 10.1% prevalence in a non-demented community population over 85 years. 1 Most new cases arise in men under 30 and women under 35, but a second peak occurs in people over 60 years. The one year prevalence of non-organic psychosis is 4.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)